Lent, like much of the Christian faith, is a joyful burden. For many of my generation and background, the twin characters of Give Up and Take Up give a gentle haunting to the approach of the penitential season.

Some people - certainly those among the marketing departments of publishers - believe reading a book is how you placate Take Up. The list of books in the Church Times – perhaps one of the few journals that give over large tracts of review space to such material – appears to get longer each year. The Lent book can be a useful discipline for the individual and group alike.

My first book, Sensing The Passion, was explicitly subtitled for this market. Two others were also pitched in that direction, albeit through the time of release rather than anything on the cover.

Some years I ago I approached the task of Lenten reading with some heightened trepidation. I was, I suppose, Lent-booked-out. I had also spent a sabbatical researching and writing a book exploring parallels between the theatre and church services.

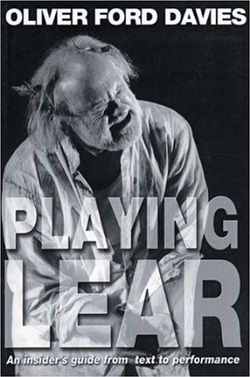

So it was that my Lenten reading took a turn. I chose two books – Peter Hall’s Shakespeare’s Advice To the Players and Playing Lear by Oliver Ford Davies. They were just what I needed. They challenged, enthused and brought me to question myself and many assumptions I had made – something any good Lent book will do.

Lent is a season when we focus on our relationship with God by trying to learn more about His grace and our selves. It is a journey that involves recognising the difference between the two. It is an adventure that seeks its expression.

It was the tangential nature of the reading that could allow me to make connections where I would normally seek to build barriers. It can involve a searing search for honesty in one’s circumstances, person or the language we use to explore them.

In his book, Oliver Ford Davies wrote, ‘I said that by the time I came to the run-throughs I thought I knew who I was, that I’d found a centre to my Lear. That feeling I never lost, and I think the key to it was language. I couldn’t really know what it was to be eighty plus, to have been a king most of my life, or to feel I was losing my wits. All that was an imaginative leap. But I did come to think that I owned the words I spoke. As Peggy Ashcroft said, ‘You can appreciate a line, but it’s no good thinking you know how to say it until you’ve found the character.’ But when you have found the character you then need the language. The two are complementary, vital partners. It’s not enough to be thinking or feeling extreme, language and action are the only ways you can express them. ‘

Perhaps that is what we are seeking in Lent, whether we read a book or not.

Some people - certainly those among the marketing departments of publishers - believe reading a book is how you placate Take Up. The list of books in the Church Times – perhaps one of the few journals that give over large tracts of review space to such material – appears to get longer each year. The Lent book can be a useful discipline for the individual and group alike.

My first book, Sensing The Passion, was explicitly subtitled for this market. Two others were also pitched in that direction, albeit through the time of release rather than anything on the cover.

Some years I ago I approached the task of Lenten reading with some heightened trepidation. I was, I suppose, Lent-booked-out. I had also spent a sabbatical researching and writing a book exploring parallels between the theatre and church services.

So it was that my Lenten reading took a turn. I chose two books – Peter Hall’s Shakespeare’s Advice To the Players and Playing Lear by Oliver Ford Davies. They were just what I needed. They challenged, enthused and brought me to question myself and many assumptions I had made – something any good Lent book will do.

Lent is a season when we focus on our relationship with God by trying to learn more about His grace and our selves. It is a journey that involves recognising the difference between the two. It is an adventure that seeks its expression.

It was the tangential nature of the reading that could allow me to make connections where I would normally seek to build barriers. It can involve a searing search for honesty in one’s circumstances, person or the language we use to explore them.

In his book, Oliver Ford Davies wrote, ‘I said that by the time I came to the run-throughs I thought I knew who I was, that I’d found a centre to my Lear. That feeling I never lost, and I think the key to it was language. I couldn’t really know what it was to be eighty plus, to have been a king most of my life, or to feel I was losing my wits. All that was an imaginative leap. But I did come to think that I owned the words I spoke. As Peggy Ashcroft said, ‘You can appreciate a line, but it’s no good thinking you know how to say it until you’ve found the character.’ But when you have found the character you then need the language. The two are complementary, vital partners. It’s not enough to be thinking or feeling extreme, language and action are the only ways you can express them. ‘

Perhaps that is what we are seeking in Lent, whether we read a book or not.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed