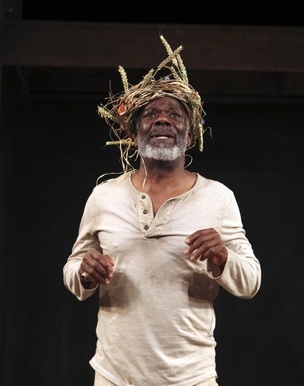

Image: Jo Dennis

Image: Jo Dennis Of the many themes in King Lear, one could be tempted to respond to the teacher’s question, ‘Frailty, sir’. It would seem a pretty good attempt. So much of the drama centres on fragility – of relationships, power, trust, physical and mental health.

One of the great attractions of live theatre is arguably its frailty. Watching the cast of a panto shatter into a titter of giggles is enlivening. On the other hand, witnessing an actor hurt themselves when a routine goes wrong breaks the artifice. Or, for that matter a member of the audience. I was at the National Theatre where a coronet cast off by Brian Cox’s Lear mistakenly hit a woman in the front row, drawing blood.

Even someone being tortured on stage should be safe. It is for that reason I can watch Gloucester - just about, as it is one of the more horrific of dramatised events - have his eyes plucked out. I know and trust that the actor playing the betrayed duke has confidence in his torturers and later will be able to see through the bandages.

A postponed blog was going to be entitled A Quick Succession. It was going to mention that changes had been announced to two advertised productions for which I had tickets. One, in Guildford, saw Brian Blessed renounce his throne after fragile health interrupted a performance. Subsequent investigations revealed a serious heart problem and he was replaced by Terence Wilton. The Malachites’ production of the tragedy transferred before it opened from the announced St Leonard’s Church, Shoreditch to the atmospheric chapel of the former Peckham Asylum.

In both productions I saw the actor playing the king read from a script. In the case of Terence Wilton, it was understandable. He had had a weekend to step into the role and, given the circumstances, the audience’s sympathy was on his side. John McEnery was not so lucky. Clearly he was grasping for the text – the programme notes’ suggestion that ‘a parallel between the ageing actor with a lifetime of experience having to search for his lines, and the aged king struggling to cling on to his sanity’ is, sadly, something of a cop out. It was tough on both cast and audience.

The reality of age is daunting. To avoid the glass house analogy, I admit that at times I struggle to find the right words to express myself – and I am not yet sixty. Also, my last professional role before ordination was marred by a hazy grasp of the third act of a play in which I took the lead. Thank God for my fellow actors who kept me on the script’s rails.

Many great actors have to face up to the dilemma of being in front of a paying public which expects, quite rightly, that they will deliver the text rehearsed. Michael Gambon is the latest to have publicly admitted this dawning difficulty, so he has announced he will only work in film and television. Live drama is, he regretfully admits, now beyond him.

None of us is perfect, but the artifice of the theatre is a collective engagement where all the participants suspend various aspects of their minds and lives. To see it repeatedly shattered in one place only draws attention to the ultimate fragility of the wooden O.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed