|

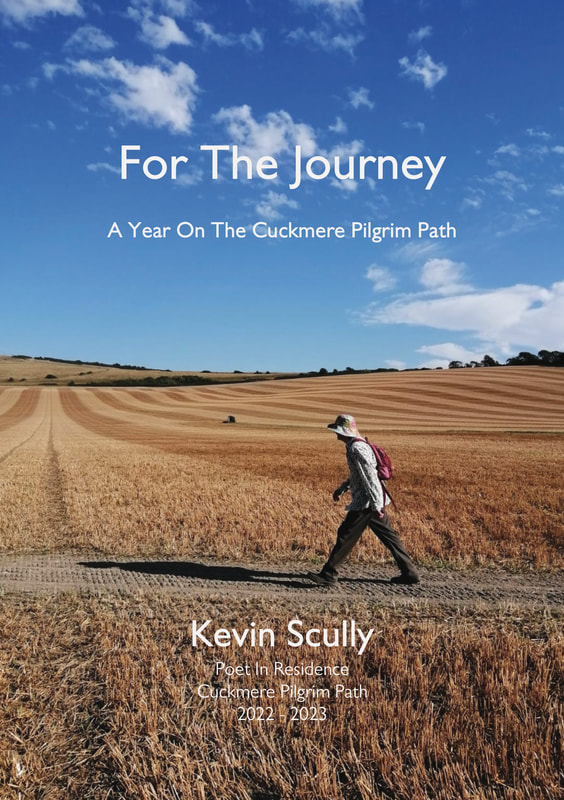

Having spent time walking, praying, talking and generally hanging out on the Cuckmere Pilgrim Path for just over a year, a pamphlet, For The Journey, was launched at an event at the amazing Berwick Church in Sussex on July 12.

That evening also involved the reading of four poems written by members of the Hastings Stanza, who held an ekphrastic poetry workshop in the church in September 2022. I read the pamphlet's poems in order of publication, which mirrors a walk around the path (with a few surprising diversions) that can be started anywhere. It was a delightful project to be part of and some of the work-in-progress was bounced off other writers as part of my MA (Writing Poetry) at the Poetry School and workshops run by the Kent and Sussex Poetry Society. Mark Oakley, author of The Splash of Words, has written: Kevin Scully's poems work like sandpaper to the soul. Unafraid to embrace the disquiet of both inner and outer landscapes, he nevertheless leads to places of epiphany and radiance. Alerting us to the locality of his residency, je makes the heart local to us too, provoking us to wonder at rumours of transcendence. Buy a copy here. This could apply to any of the pages of this website, but I have opted to air my views on this from a personal POV on my Poetry page.

Thanks to the wonderful Karolina Krasuska. The Church of England tries its best. I am glad it does.

It ordained and deployed me until my retirement and I still serve its fragile loving presence in the country. But sometimes its blinkered nature, be it through privilege or an intolerable attempt to include the irreconcilable, makes it as wise as King Lear or the Earl of Gloucester in Shakespeare's tragedy. To that end, I have suggested an Ecclesiastical King Lear. Let's see what the bishops at the Lambeth Conference come up with... ‘God said it. I believe it. That settles it.’

This was the text of a bumper sticker a friend of mine saw some years back in the United States and it caused us, weak minded liberals that we are, some amusement. Yet such a statement is indicative of much of what is going wrong in the discussion of ideas. It should not be taken seriously. Claims of truth, being woke—once a term of approval which has morphed into the pejorative—no platforming, accusations of censorship, freedom of speech: all have a painful interconnectedness that too often goes unchallenged. It does so because it takes patience, rigour and intelligence. And yes, even weak minded liberals can run short of these three elements. I used to travel to away football games with a group of friends. It was a pleasant way of spending the hours on the road or train, talking, stopping for (or bringing with us) a few beers and a bite before the highs and lows of watching the team we support. These trips became somewhat uncomfortable as one of our number started voicing opinions which, when countered, were responded to with an increase in volume. Given his innate gift for projection, usually in outrage at some event on the field of play, he would quash opposition. No arguments would be offered. Simply a louder restatement of what he had said earlier. His views were and are outrageous: humanity is descended from aliens, the moon landing was faked, there is a conspiracy to deny white people access to public housing and jobs. Yes, the usual suspects. In recent years the public square has seen a diminution of trust which, it may be argued, was never that high. A privileged out of touch cadre of politicos schooled in their own ways in cloistered environments to live in a luxury of subsidy and isolation from those who both fund and vote for them. There are all sorts of reasons for this: the rise of populism, the control of messaging information, the lure of unchallenged power. A spin of the globe, a touch of the finger and you are never too far from this enmeshed web of difficulty in discerning not only what is going on, but how it is being related. Writers are told to stick with what they know, so I will confine myself to Britain and the United States. There can be little doubt that the current front bench of the Conservative government is one of the most lacklustre to have been drawn from its ranks. Built on a rabid belief in Brexit, which was and is being sustained on a tissue of lies and fabrications, the culture of dishonesty, ineptitude and corruption is jaw-droppingly astounding. How do they get away with it? Well, simply they have a massive majority that shows that those who bothered to vote in an electoral system that, surprise, surprise, benefits those elected were, by an large, in favour of leaving the European Union. The legacy of the referendum, needlessly called by a schoolfellow of his predecessor but one, was aimed at sorting out differences within the party. And it has managed to split the nation. This is not just political parties. This view has been supported by the majority of British papers, notably the Daily Mail and Express, which are part of the network of connections of the rich and privileged that seek to govern the country. Rupert Murdoch has abandoned any pretence of objectivity in his media outlets. He is regularly feted by would-be leaders of countries in the hope he will throw his ‘empire’s’ weight behind them. It is perhaps not without irony that the current administration in Westminster is heavily weighted with people who are or were journalists. The Prime Minister is one, was paid a bomb for very ordinary articles by the Daily Telegraph, was sacked for fabrication when working for The Times. His current wife, number three in a series of wronged women who have borne the philanderer children, is one. His staff of special advisors have a few and only one, Allegra Sutton, has been offered up as a sacrificial lamb. The public view of politicians and journalists has always been questionable, but the UK government’s mix of the two is perhaps no accident. When I worked as a journalist there was a pride in seeking to be as clear and correct as possible. Sure, every organisation had a line but it sought, not always with success, to separate news from opinion. In over 20 years in the game, I rarely read a leader column. They were all too predictable. The union of which I was an active member had a Code of Ethics, which sought to inculcate some kind of structure of standards and reliability in going about newsgathering, interviewing and representation of views. Increasingly, because of changes in how we access information, the fourth estate has become increasingly marginalised. In an effort to get where people want to source their opinions they have gone online, into social media and created what is derided as clickbait culture. In this people choose the rabbit hole they jump down. This has, to a certain extent, always been the case. Choice of news outlets is often indicative of one’s leanings. A research project into two samples of young Muslims and Black Pentecostal Christians in London by the academic Daniel Nilsson deHanas is illustrative of both identity and what influences people in choosing sources of ‘news’ on which to base their opinions. The research looked at how members of the two profiled groups classified themselves by race, religion and place in British society. It also highlighted a similarity on how they sourced information from which they made decisions about life, lifestyle and politics. It should come as no surprise that they relied substantially on other people they knew, ostensibly from their identified associative groups, to base decisions on what they bought, who they might affiliate with and, if they could be bothered, who they voted for. This is based on whether their networks had agreed (by which processes?) the sources were reliable. The project shows the way our worlds can shrink. Lest anyone want to gloat over a generational divide, it is worth looking at one’s own contacts and friends and analysis is likely to come up with similar results. And, to return to the cadre currently in the government benches in Britain, we should be rightly alarmed at how small these circles are. Gaby Hinsliff, in a review of Sasha Swire's scandalously revealing diaries, writes and quotes from the book: ‘Swire is at least vaguely aware of how insufferable it can seem; glancing around the Camerons’ Downing Street Christmas party in 2011, she realises “we all holiday together, stay in each other’s grace and favour homes, our children play together, we text each other bypassing the civil servants … this is a very particular, narrow tribe of Britain and their hangers on.” By 2015 she is fretting that Ed Miliband is clearly “on to something” in pledging to abolish non-dom status and that the Tories have become too harsh towards the poor, “unforgiving of personal circumstances, relentless in telling people to stop whingeing and make a go of it”.’ In a plethora of stories about the misuse of power and betrayal of trust levelled at the Johnson government, one example suffices. The ‘Waiting For Sue Gray’ as an ‘independent’ inquirer into the culture of parties at Number 10 Downing Street is dubious from the outset. A civil servant is investigating the behaviour of residents and staff of Number 10, will make a report to the Prime Minister, who is in charge of the ministerial code and is himself one of those who actions are up to question. ‘How insufferable it can seem’. Conspiracy theorists, limited thinkers, exclusionists all use such networks, personal and communicational, to learn, take on board and spread the ideas. These notions range from the mildly amusing to the delusional and dangerous. ‘Facts’ are often no more than hearsay. I watched an horrendous video where someone who had breached the confines of an ICU where a family member was being ventilated following the contracting of Covid-19 seek to justify the ‘myth’ (i.e. falsity) of the disease because someone somewhere had written something. This was considered substantive proof of this piece of ongoing chicanery and the family members repeatedly asked for the discharge of the patient. . It is no surprise that a rich, powerful man who challenged and succeeded in being elected to high office used terms as 'fake news', his spokesperson talked of ‘alternative facts’ maintains the fiction that his loss in an election was about it being robbed from him. His followers lap this stuff up and the result was the storming of the Capitol building in Washington in January 2020. One of the most alarming images for me was the erection of a cross as part of the demonstrations. It linked faith in Christ, however that was understood, with the madness of opinion replacing belief based on evidence and fact. Facts, no matter what we think, remain facts. For my sins, I am a Christian. I would love to say that my faith is based on more than parroting some kind of arcane formulae but the communion of which I am a member has a tradition of, and a problem with, tolerating contrary opinions, some of which, to be frank, do not and can not hold together. And I know from my studies in the Philosophy of Religion that it is easier to disprove the existence of God than it ever will be to show the contrary. Mind games have rules, a consistency and once you accept the premises, argument must run on the tracks laid down. Religion, for all those who try to do so, is not going to be proven by argument. It is about how we engage with our texts, traditions, heritage and the world around us. Even the Church of England, with its much vaunted breadth and dying tolerance, embraces such madness as fundamentalism, though it is usually attired in more respectable clothes. Churches claim to be Bible Believing but all churches should be able to use such a phrase. It has of late been changed to Bible centred, but it is the same problem. Just claiming scripture is God’s word, irrerant, factual and reliable is not enough. Repeating assertions as to what God said as authority is open to question. A check of online websites devoted to this cult of belief is instructive. This one shows the circularity of the argument. And this is perhaps the danger of what we face. We decide how we act on what we think we know and the sources of this knowledge. Barack Obama said the world faces ‘an epistemological crisis’. Christianity can contain a strong strain of refusal to engage in debate. Untested assertion is merely opinion, unreliable until tested. Fundamentalists, in my view, seek to close down any attempt to speak about source material, using critical tools and even question methods of interpretation. This intellectual intolerance has shrunk trust in the public square and is worked out in conspiracy theories. What I believe does not constitute fact. I need to question at all times information, its sources, and decisions built upon it. ‘God said it. I believe it. That settles it.’ As the audience cries out in a British pantomime, ‘Oh no, it doesn’t!'  Why do bullies get away with it? This simple question is one for all of society, though it is most used in the context of schools. But bullying can happen anywhere—at work, places of worship, clubs, social settings. It often dresses in different clothes: misogyny, racism, nationalism, tribalism, religious intolerance, class distinctions, privilege. One place where bullies work to the greatest effect is in football. Recent focus on the beautiful game has revealed the re-emergence of the dormant ugliness of some of its supporters. No matter how many good slogans and campaigns come down from the top of the game, the place it needs to change most in its ‘fans’. I have had the joy of supporting a lower league football team with all its travails for over twenty years. And I would love to say that the welcoming, accepting atmosphere that I found among people at Leyton Orient was universal. But that would dodge the issue. I know, from experience, that the sickness is not ‘out there’ but within. I recall some years ago coming home on an evening train from Cambridge, where my wife and mother-in-law had spent the day visiting friends while I was at the football, and seeing a carriage reduced to trash. I recognised, and still do, some of the faces of people I had seen at home games as they tore seats, smashed lights and bottles before setting off a fire extinguisher. It was frightening. And being in the next carriage was not a sufficient barrier. My fellow passengers and I passed anxious looks. Should we intervene? What support did we have? There was no conductor on the train and at the next stop a few of us made our way to the driver’s cabin and reported the incident. We got back on the train, having removed ourselves from proximity of the scene of devastation, and the journey resumed. It was about three stations later, long after the damage had been done and the guilty had dispersed throughout the train, that the police boarded and came through the carriages. No-one, not even the man sitting up from me, who I knew had been part of it, was nicked for the vandalism. Did I stand up and accuse him? No. Why? I feared for my safety. I knew this chap was not a lone wolf, but part of a pack that would regroup further down the line. And if I could recognise them, they would certainly recognise me. Like many bullies, they got away with it because the victims and witnesses did not believe there would be a rigorous response that would protect their vulnerability. I reported this incident to a friend I sat next to at Brisbane Road, a lovely chap I had met when I baptised his granddaughter, and told him that I was going to stop coming to the football. If people like us stop coming, he said, the idiots take over. This was the same man who rescued me from accusations of paedophilia because I had come straight from a church function, dressed in my clerical clothes, to a game. That came out of the blue; I was simply queuing to get half-time refreshments. I have stuck with it. But it is an uncomfortable adhesive. In the past six weeks, I have been to a number of away games and I have either directly witnessed or heard of incidents of abuse to players, officials, fellow supporters, and people who support the home team. The make up of the crowds is a good indication about what is wrong. As a keen theatre patron and football goer, I have seen similar trends: increasing diversity among casts and teams, with no concomitant significant visible shift in the backgrounds of spectators. Why might this be? Having heard Asian people derided in a chant on a train coming home from a game at Millwall, perhaps the most hardcore and vicious practitioners of football bad behaviour, (though some of the nicest people I have ever met support the Lions), I was distressed. The bloke sitting opposite me, with a young lad next to him about the same age as the boy with me, said in some astonishment, ‘You’re an Orient fan, aren’t you?’ I nervously outed myself and was able to raise my objections to the chant. ‘It’s only a bit of fun,’ he said. And herein lies the problem, the negation of culpability because it is banter or adds to the atmosphere. It does not. At a game at Carlisle a man sitting behind me (I had to move) spent more time effing and blinding and accusing the other side’s supporters of onanism than watching the game. He was nasty, vulgar and crass. And he was having a ball. There are routine chants at Leyton Orient from some fans about how they ‘hate’ those bastards in claret and blue. Towns are derided as shit, their residents are designated ‘scum’, ‘wankers’, ‘pikies’ and ‘poofs’ and, when in university towns, ‘students’! There are lots of Fs and Cs thrown in for good measure. Should their voices be drowned out, there are many hand gestures, one in relation to masturbation, that take their place. This behaviour is not just for the hardened. I have seen children as young as seven using the language and gestures and then look for approval from their elders. They are rarely rebuked. Goalkeepers get the worst of it from supporters behind the posts. At a game in Bristol recently, the home keeper was abused, told he was shit, slagged off and belittled by a man further down from me. If anyone else was subjected to such abuse, and that is what it is, while merely going about their business, the perpetrator would rightly be held to account. But it is justified as it usually is, just a bit of light hearted banter that adds to the game. After all, they will tell you, it’s part of the territory of being a goalkeeper. The same game saw a steward racially abused by Orient supporters for doing nothing more than his job. I had the report second hand but it was given to me by a friend who, by his own admission, ‘could never be accused of being a liberal. But it was out of order.’ Was the incident reported? A check with the club management confirmed that they had heard nothing about this. As for referees and linesmen, they get a torrent of abuse for when they make decisions supporters think are biased or unfair. Many of us have joined in the booing of officials. Only later do I think this may have been a form of bullying. A couple of weeks later Lawrence Vigaroux, Orient’s man between the sticks, was subjected to racist online abuse similar to that meted out to three black footballers who missed penalties in the England-Italy Euro final defeat. The person received a ban from the home club, Port Vale. It was reported the Euro abuse was by someone who attended Orient games. He received a lifetime ban. At home and away games there are a number of Os’ supporters who would boo when players take the knee. It is true that they are very much in the minority, but they obviously feel comfortable in doing this. This is bigger than ‘culture wars’ or ‘wokeness’; it is about what is acceptable to people going about their jobs, and the enjoyment of others for what is, after all, only a game of football. A number of players and clubs, Orient among them, have not made the gesture as they believe it has not had the necessary corollary. Is it any wonder that some people are intimidated by going to the grounds? It is well attested how popular football is among many communities, yet their presence is limited in the stadia. The ubiquitous England flags, usually with a club’s name or insignia, that are draped by away fans at games are more than tribal signals. They are the fruit of a deep illness within us. Lest this becomes an epistle written with a stone before casting it through my own glazed residence, I own that standing up to a 16 stone drunken, swearing oaf as I know if it gets physical (as it rapidly can) is not my idea of a good day out. Nor have I always been the person I am who, I hope, is open to change. For my sins I was, by virtue of my upbringing and background, a bigot, though I did not realise that at the time. I was simply asserting what was the accepted ethos. After all, the country I was born in had a White Australia Policy, and the sins and crimes against its indigenous people were not even mentioned. They are more than enough to repent of. Through my work, training and vocation as a priest, I have had to challenge many accepted norms but no doubt being white, male, of a professional background, and in a role that still has a burnished sheen of respectability softens my perceptive radar, I have learned that we have to challenge ourselves internally and externally. During a recent discussion with a diversity champion in the arts, who happened to be a Tottenham season card holder, he took issue with my concerns about the make-up of crowds. The changes that he says are more instrumental in substantive change come in management, in the boardroom, in the who and how of running of a club. That is where institutions are changed. It is why our society, the church and so many other organisations fail to implement ‘the lessons to be learned’ that follow every investigation of a scandal. Until we change the structures of organisations, we should not be surprised that they make the same mistakes. Which is why I now report, when I can, the ills I see. I call out comments, I make myself unpopular and my nickname has changed in some parts from Revkev to Redkev. Why do bullies get away with it? In a version of a saying in various forms attributed to Edmund Burke, Thomas Jefferson, John Stuart Mill and a number of others, ‘Bad things happen when good people stay silent’. It is important to speak out and recognise the illness within us and around us. Only then can we really Kick It Out.  Pat Grummet Pat Grummet This is a first for this blog. I often quote others but I was privileged to be among a number of interviewees for a short project that the fabric artist Pat Grummet undertook recently. She, at the age of 87, is a member of a group looking at various aspects of textiles and life, each of whom presents a short paper for discussion. Pat happens to be my mother-in-law and has been a creative, artistic and spiritual companion. Her paper, Dress Ups, follows..... For a small child the dress-up box can occupy many happy hours. There are endless treasures to be discovered and characters to be created through combining, sometimes incongruously to the adult eye, a random selection of elements. A good dress-up box can contain hats, aprons, skirts, discarded clothing, pieces of fabric, bed-sheets, scarves and shawls, costume jewellery, handbags, hats, shoes, glasses. A child from four to five years-old can create a magical world of make-believe. However, role-playing is important for the child’s character development. It engages the imagination, builds vocabulary, develops sensory and motor skills, develops empathy and cooperation with others. A child, female or male, can explore gender identities, vocal range, and memory. I spent some happy hours in lock-down with a number of friends, reminiscing about dress-ups in their own lives. There were stories of children who loved to dress up, and the ones who hated it; some would enthusiastically wear their dress-ups in public, and some were too embarrassed to be seen by others; of mothers who could sew, and those who couldn’t. School Book Week was an opportunity to be one of the characters a child related to, dance classes and theatre productions were a chance to be someone in another story. There were recollections of cowboys and Indians, Annie Oakley, animals, insects, TV and movie characters. The advent of television brought visual impressions of character, and in a way put parameters around “what ought to be” in terms of colour and movement. Commercial enterprises saw the chance to exploit the decrease of sewing skills in the wider community. More interesting, I found, was the collection of random pieces that could be thrown together to express mood, temperament, and fit a spontaneous story-line. Friends spoke lovingly of long, swirly skirts – red, black, yellow, pretty floral. A red velvet cape could be Red Riding Hood or Superman, or a magician – perhaps with the addition of a hat. Scarves and net curtains could be tied around the head as pretend hair, beach towels created sheiks. Superior ladies wore hats, gloves, and perhaps a fur stole, feather boa, or a muff made out of an off-cut of sheep-skin. Common garments were put on different parts of the body – socks on the hands, underpants on the head. Old sheeting could create a ghost or a monster, or be torn into strips to make a hula skirt. Fragile butterfly wings simulated flight. When asked to recall fabrics, movement, flow, and touch were remembered. Satin, velvet, and fur were favourites. Silkiness was enjoyed by both girls and boys. There were three stories of boys nine, ten years and older loving the touch of silk. People enjoyed shiny things - tinsel, sequins, as well as gossamer transparency and weighty taffeta. One friend has enjoyed a life-time of dressing up, from a childhood writing plays and sharing clothes in his large family. He loved his regular role as an altar-boy in white surplice with lace, and red slippers. From training as, then becoming a professional actor, he later turned to the priesthood. He wore black every working day, breaking out into colour on days off. Always unconventional, he now finds a great deal of joy in putting together the wildest of outfits, combining many colours and designs to enliven his retirement. Dressing up is part of a search for identity, using role-play to decide between good and evil, old and young, male and female, teacher and student, buyer and seller. Children gradually work out their place in the world and their relationships with others. As adults, that creative play can last us a lifetime. © Pat Grummet 2021 Being condemned for what you have not been able to achieve is sadly something priests get used to. There is always some aspect of the proclamation of God’s love for everyone in word and sacrament that someone will take amiss. And those people often feel the need to let an individual know.

Clergy, in most cases, don’t need much kicking to stay down. They are pretty good at knowing how far they fall short of the standards they would like to achieve but their job is generally considered impossible. According to Michael Ramsey, someone who would hardly have shone in today’s managerial churchspeak, the priest’s job is to represent: to represent the world to God, and to represent God to the world. Such a job description is essential, but it does go against the ‘we are wonderful’ zeitgeist of church planting, self-reference and congratulation. It is inevitable that the publicity over clergy and buildings being described as limiting factors by someone who has already nailed his ecclesiastical sectarian colours to the mast of the good old ship CofE will be seen as another kick to an already battered profession. As others have pointed out, this stems from the confused (and some claim blessed) nature of comprehensiveness that the Church of England seeks to enflesh: those who believe contrary aspects of doctrine quietly grumping at each other in love and pain. The church has tried for centuries to reconcile the irreconcilable and being a limiting factor is just another arrow in the quiver to shoot from the bow of controversy. The main problem is ecclesiology. Lots of paradigms have been painted and will continue to be etched on a canvas that some would say is already overstretched. It was over twenty years ago that I was asked by a bishop to be the Director of Ordinands and Vocations Advisor to an area of London. In that relatively short time I witnessed what I can only describe as a programme of putting forward people who had been coached to say things that they did not believe to allow them to go through the process of consideration for training for the priesthood. Please take note of that word, priesthood. Time and again, it became clear to me that these people did not really believe in either ordination or have softer loyalty to religious tolerance, but owed allegiance to a sectional and partisan approach that defined the breadth of God’s love. This was usually revealed in discussions about Biblical interpretation, sexual identity, authority and the purpose of the church itself. This took place at a time of burgeoning power between two groups who described themselves as evangelical: one which may made claims about the Bible that were beyond fundamentalist, and another that had a particular expression of charismatic gifts. Both had their own system of apprenticeships, inculturation and preparation for dealing with officers like me whose job it was to discern suitability for the ordained ministry. More than once I suspected that these would-be candidates did not really believe in ordination but were prepared to do anything to get into what soon was no longer said—‘the best boat to fish from’. Another peculiarity was having to provide the same process for another sectarian group, ‘traditional’ catholics. These candidates were often older men whom the church had earlier discerned were not really suitable for priesthood or young men who had a particular predilection for church accoutrements and vesture that seemed frozen in time. Both were united in their rejection of women serving in the church as equal colleagues. Again, they went through the processes and, often despite my clearly expressed reservations, the bishop responsible for this splinter group, would send these candidates to selection conferences which, more often than not, agreed with my summation, only for the purple shirt wearer to overturn the decision and ordain them anyway. More than once I said both publicly and privately, ‘Why bother with this farce?’ Admittedly I am not isolated from these issues. I am a liberal catholic who has also been part of ‘sectarian’ group, The Society of Catholic Priests, for 25 years. Not surprisingly, after a while I thought serving the church in this way was not either the best use of my time and talents, such as they are, or good for my blood pressure. I opted to serve as a limiting factor to a broken congregation who had the stewardship of a crumbling plant in what was then a difficult area of London. Things change and, to no-one’s surprise, ‘successful’ churches wanted to move into the area when the demographic started an upward financial shift. Plants have sprung up. That the church now finds itself pushing at the seams of a garment that so many wearers clearly are not suited to is hardly surprising. And in all this, we need more churches that show the diversity of the world which reflects the breadth of God’s love. How to get around this? Oh gosh, let’s get rid of discerned, trained and deployed clergy and free the gifts of everyone to do as they wish. The Church of England has its ongoing catastrophes of safeguarding, institutional racism and, as I have pointed out before, entrenched protectionism of privilege—has a bishop ever faced a Clergy Discipline Measure? The growing planting church movements are invariably male led, authoritarian and self-referential. Don’t be fooled by the lack of dog collars. These ‘ordinary’ blokes just love to be in charge and that’s why they want it to grow in their own image. How did we get here? Historians will be best placed to analyse this but I would suggest one aspect of the crumbling ecclesial structures can be understood through the lens of Trotskyite entryism. Entryism, to quote the Oxford Reference website, is a ‘term given to the tactic pursued by extremist parties of gaining power through covertly entering more moderate, electorally successful, parties. Within those parties they maintain a distinct organization while publicly denying the existence of a ‘party within the party’. Diarmaid MacCulloch, in his magisterial Silence, A Christian History, says, ‘It is a melancholy truth about the human race that groups who have suffered oppression are inclined to forget the experience, once given the chance of power.’ Church politics are not estranged from power struggles. Just look at what has gone on to protect certain people in high places, its failures in providing a safe environment to the vulnerable and to deny racial justice in terms of finance. So let’s set sail under the canvas of a ‘mixed economy’. I know from personal experience that ‘leaders’ of plants and some movements show disregard for institutional governance, with bishops and authorities pandering to them for who knows why. Some of them have even climbed up the pole of ‘preferment’. One told a startled chapter meeting that he was worried by the lack of women in their leadership team, so they ensured the wives of the ordained attended staff meetings. You can imagine the reaction when I questioned this saying, ‘I was unaware that sleeping with the vicar is now a part of discernment for public ministry.’ You reap what you sow. There is an existential crisis in the church which, in its wisdom or madness, selected, trained, deployed and has pensioned me and others to serves in its ordained ranks. I look with pride and discomfort on what I have done. Perhaps it should come as no surprise that many movements within the Church of England claim they are not churches within a church, despite having their own customs, structures, conferences and politics. It is part of the warp and weft of diversity. But there comes a time when a fabric will not stretch further. Maybe it is up to the fashionistas of church politics to decide what they wear. Have I been successful? Perhaps. Have I failed? Certainly. But on a daily basis I have sought to pray and serve the world which God has made, sometimes within my comfort bubble but, more often than not, outside of it. No wonder I, like many of my colleagues, feel I might have let the side down. Yet still, day by day, I pray to the God I believe is bigger than the restrictions I and others place on love, acceptance and wonder. As Gerard Manley Hopkins put it: Glory be to God for dappled things – For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow; For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim; Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches’ wings; Landscape plotted and pieced – fold, fallow, and plough; And áll trádes, their gear and tackle and trim. All things counter, original, spare, strange; Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?) With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim; He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change: Praise him. What does it take for an institution to reform itself successfully?

This question is before many boardrooms, political parties, union meetings, community organisations, Parochial Church Councils and focus groups. The more radical any proposed solution is, the more it involves facing critical issues. The Church of England has in the past both been able to spearhead change in some areas of its life, while becoming ossified in others. Its latest shortcomings – abuse, racism and the Clergy Discipline Measure to name but three – only serve to highlight its difficulties. The desire of some of its members to look both ways is not helpful. Sometimes such action creates a false ‘inclusivity’. This can be seen in the process that suggests the Church allows women to flourish in the ordained ministry while instituting a procedure that allows the selection and deployment of those opposed to their very existence. Pointing out such things makes one liable to accusations of extremism or even cultural Stalinism. But radical measures are those which were advocated by Jesus only for them to be repeatedly subverted by institutions devoted to following him. They can reflect many toxic attitudes. I want to put forward three propositions, each in its own nature provocative and potentially outrageous, that may help the Church consider where it stands on its principles and practice. They relate to memorials, graveyards and marriages in church. The ongoing failings in relation to people of colour, highlighted again in From Lament to Action, can be seen in the heritage of memorials in church buildings. The very presence of any of these creates difficulties. The church I served as parish priest in London for 17 years had a single surviving memorial on the church, the rest of which had vanished in the clear up and restoration after Second World War damage to the inner city. Visitors would often remark on the contrast of the 18th century building and its striking 1960s interior. When asked to account for this, I would quip, ‘Thank God for the Luftwaffe’. The memorial by the entrance was deteriorating badly and the inspecting architect counselled its removal for storage in what was left of the crypt. This freed the building of memorials—none had been installed since refurbishment—allowing a freedom to worship or look at the extraordinary art that accompanied reconstruction. Likewise, there were only two graves in the churchyard. One was maintained because of a legacy to an organisation that had benefitted from a man’s philanthropy. As is often the case, his good works may be considered questionable in the light of how his money was made. The second was of a family member of someone called The Boss of Bethnal Green in a book by Julian Woodford. Needless to say, the Boss had a colourful history, including a convictions for running bawdy houses and misappropriation of funds. The rest of the churchyard was clear of headstones, once again because of the damage suffered in World War Two. I know of a Home Counties church that has two memorials of Crusaders. One has the decapitated head of a Turk as a pillow, the other has a cartoon-like Muslim as a footstool. I expect in time such memorials will rightly become as problematic as those of slave traders. Memorials and, to a lesser extent, graveyards pose problems for a Christian. If we believe in the radical equality proclaimed in our faith as typified in the letter to the Galatians, why does the Church tolerate such testaments to human vanity? These are mostly vestiges of a financial consideration. Of course, work needs funding and realpolitik would suggest there is a quid pro quo. But does the Church unduly compromise itself in this? Gravestones do not help the Church in its oft stated mission about the sacred quality of nature. Parks, natural burial centres, and the like would be of greater use if they provided either open space or natural habitats for species of plants, birds and animals. This is not to ignore the needs of people needing a place to go to remember their loved ones, but a walk around many churchyards serves to remind us of the past and the here and now. This construct of destructive human need takes precedence over nature or eternity. The last thorny area of activity is in relation to marriage. The latest changes to registration practices in the Church of England do little to clarify the mess that it is in over relationships. The current practice which allows marriage between certain sections of the population while denying it, by regulation or clerical conscience, to others is not sustainable. Once again there is a heritage of power, privilege and financial gain. If the Church wants to have an open doors policy, then implement one. Follow the French, Dutch and German model, get civic authorities to conduct all legal and registration procedures and those who want a religious element are free to have one. Divorce, remarriage, same gender partnerships can all then come under the open arms of God’s love. This proposal is not a new one from me and may be met with the usual reactions of seeking to destroy ‘Christian’ marriage. As has been pointed out before Jesus’s only consistent teaching was in relation to remarriage, but the Church has long since resolved its quibbles on that score. Of course, each of these issues qualifies for sailing under a flag in the current cultural wars. And yes, such suggestions will be fraught with ‘practical’ difficulties. But reformation, which is what they amount to, needs to be confrontational and revolutionary. There will be lots of arguments and reasons to counter these proposals. The responses will be, in many ways, predictable. But if the Church wants to move forward, how far will it go in changing itself beyond planting more middle class congregations aping ‘informal’ services? Is it prepared to be as radical as the early church was in being for the good of all, and ensuring no-one is in need?  Some relationships are fundamental: parent, first lover, spouse, child. For clergy it can be a training incumbent (TI), a recent designation for the senior member of the clergy who oversees a curate. Such pairings have all the delights and dangers of other fundamental relationships. They involve transference, admiration tinged with envy and anger; or they can sour so quickly that the curdling ruins not only the way the immediate circumstances are handled, but the future. Allan Scott was my TI. He also became a friend which, like all good friendships, had contradictory elements. He taught me, he infuriated me, he coached me but, above all, he showed me a model that I could accept, adapt or reject. Inevitably I did a bit of each. One aspect that became a plank of my ministry was that of end of life, death and funerals. By the grace of God, I felt a special calling to this and it has featured substantially in whatever faltering steps I have made as a priest. Allan showed me the practicalities of anointing and the last rites. It is a privilege and honour to administer these but even more so when I was asked by Allan’s daughter, Anna, to do so for the man who had trained me. I did not do it according to Hoyle but do it I did. It was only later that I realised I had also commended my father to God’s care when he died years earlier. It is not my practice to publish sermons—at least, not in the form they are originally composed. My first couple of books started as Good Friday addresses. In the happy coincidence of personal connections that can govern publishing, I mentioned the substance of one to an editor over a dinner. She asked for a pitch and I was delighted to see the transformed text—experience in broadcasting and print had taught me the original of one form does not suit the other—on display in a bookshop window. All of which is a long apologia for presenting what follows. It was delivered at Allan’s funeral on February 8, 2021. A different take on it can be seen in the obituary I wrote in the Church Times. Rest eternal grant unto him, O Lord… 'He was a bugger, but he was a bugger on the side of the angels.’ So said a long-serving clergy colleague from the Hackney Deanery, in which Allan Scott served for more than 25 years. It is not my job to canonise Allan or to condemn him. It is my hope to relate something of his life and to shine a light on his faith and see how that might relate to us. We are greatly helped in the readings that have been selected for this requiem because the first and foremost responsibility for those in the catholic tradition is to pray for Allan and for the repose of the soul. Of course, this can seem odd that we would trouble the gracious and loving God with any concerns or supplications we have, but it comes from a deep-seated belief that is echoed in the story of the raising of Lazarus: that our brother is not dead but alive in a form and way that is beyond our understanding. How did this life start? Just over 81 years ago, Allan (with two Ls, please) George was born in South Shields, the only child to parents he said died young. From that beginning he held tenaciously to his working class roots, no matter how arty-farty (a derogatory term from his lips) his tastes and lifestyle might have become. He was steeped in the Anglo-Catholicism of the north-east, which can be somewhat more grounded than the sometimes rarefied expression of it in other places. It engages with place and people and work, a key expression of Allan’s understanding of mission. What is the reality of the place we find ourselves in? And of the people among whom we live and work? How can we move that and them on to grasp the challenges of Jesus in liturgy and its outworking in society? Clearly for Allan this saw Christ’s transformation of society in a particular way. It takes the dead and seeks to convert it to life. He was a Socialist and a Christian, two aspects of his vocation which developed through his studies at Manchester University and priestly formation at Mirfield. He was ordained in 1963 and served his title at Bradford cum Beswick in Manchester. Unusually for the period, he went on to become Priest-in-Charge of the parish. He surprised many by leaving stipendiary ministry to work for the newly formed charity Community Service Volunteers, now Volunteering Matters, seeing the transformation of young people’s lives as a priestly calling. He also served as an honorary priest in Bramhall and parishes in London. Having married Elena in Sofia, Bulgaria, in 1969 – their union led to the arrival of two daughters, Christina and Anna - he returned to parochial ministry when he was made Rector of St Mary’s, Stoke Newington. I want to pause there for a moment to highlight Elena’s support of Allan in his ministry. An intelligent woman, she supported him in many traditional roles while holding on to her independence. And to the girls he was, as he remained till his death, their Daddy. This should not surprise anyone, though many may have seen the sometimes hard, angular Allan in a different light. That is important for us to remember today. Each of us has an angle, a view on an individual. It is inevitable that one’s experience or exposure dictates our memories but they can never be the whole picture. Only God has that. Allan had a prophetic, mercurial and sometimes exasperating nature. Deeply intelligent, compassionate, caring, and dogged, sometimes to the point of a bluntness that could seem hurtful, he always sought to see the broader picture. His voracious reading and enthusiasm were all part of the mix. Such was his commitment to discussion that if he had a point to make, or he disagreed with you, he would stop in his tracks while he walked, turn to face you and point that accusing finger that was so much of his weaponry. He was committed to the development of the spiritual wellbeing of individuals in his care. Retreats, courses run by members of the congregation, not the clergy, and sometimes by those outside their circle. He involved parishioners in liturgy, and sought to deepen their prayer lives and involvement of the church in its wider roles in the community. And there was the visiting, visiting, visiting. The offices were central to him, the presence of Jesus in the blessed sacrament, a devotion to our Lady, all the catholic expressions of a faith that he wanted others to grasp and grow in. He was detailed and arguably controlling in many of the wider parts of the parochial task: finances, organisation, meetings. Oh, those meetings! He would keep the most controversial elements till last. They went on far too long for my taste and one time I stood up and headed for the door. ‘Where do you think you’re going?’ he said. ‘To the pub,’ I responded. ‘It’s last orders in five minutes.’ We had been at it for nearly three hours since the mass had finished. Impossible to think of a PCC without a celebration of the Eucharist. While intelligent and thoughtful, he could be as stubborn as the proverbial mule if he had made up his mind on a point and others did not agree with him. I won’t rehearse the times he and I locked horns but they both great fun and sometimes bruising at the same time. There were many things we did not agree about, such as the role of women in the ordained ministry, but it was a privilege to remain in close contact with him since he was my training incumbent, as he was to many others. He also nurtured and put forward a number of women for the ministry despite his reservations. He had a gift for friendship and, unlike many clergy, had no qualms about being friends of those in his care. He drank too much, liked to socialise and party, ‘a feast of rich food, a feast of well-matured wines’ (Isaiah 25:6), was very much to his taste. And work. His retirement project with Chomok Ali in the manufacture of clothing – often of high fashion – led him to mix his management skills with schmoozing on behalf of New Planet Fashions. He enjoyed all that and the shabby Allan that many of us knew transformed into a well turned out businessman. All of this, of course, was under the searing arc of God’s love which calls us out of darkness into light, out of the shadows of death into light. Allan had his foibles—we all do—but he was passionate in serving God and wanting to share his understanding of how the life of Jesus could be transforming and transgressive. Jesus acted quite oddly when he heard the news of his friend Lazarus’s illness. He went away, ensuring he would die, before going to visit Martha and Mary, the deceased’s sisters. In some ways, the division of labour of those sisters was reflected in Anna and Christina. Anna being on hand in person, Christina in Beijing the long distanced organising. Like the family of Lazarus, there have been ups and downs, with a highlight being his 80th birthday with friends and his daughters not all that long before his stroke which left him an invalid. When Jesus stood at the tomb of his dead friend, he wept. ‘See how he loved him’. This is the love God has for us all. Particular, sometimes regretful, but powerful. So powerful that in this case Jesus calls Lazarus literally out of the grave and tells those around him to ‘Unbind him and let him go.’ God in Jesus does this for all of us. He may not respond to our agenda, doing what we want when we want it. But he calls us in love, a love that can shed tears, a love that took him to the place of deepest and darkest suffering. And, like the friend he called from the tomb, he burst from his own to call us again, to come to him and be part of that transforming life. ‘Who will separate us from the love of Christ? Will hardship, or distress, or persecution, or famine, or nakedness, or peril, or sword? ….No, in all these things we are more than conquerors through him who loved us. For I am convinced that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor rulers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.’ (Romans 8:35-39) - delivered at St Alban’s, Holborn on Monday February 8, 2021 |

Thoughts from the mind and keyboard of Kevin Scully, writer and priest.

All content © Kevin Scully Header images courtesy of Adey Grummet

Archives

January 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed