Poetry is a Scully family thing. My father Ken, whose work also appears under the name of John Dawes, wrote verse throughout his life. As he edged towards death, one of his children was despatched to the ramshackle wreck that was his office to fetch and present a sonnet in honour of his wife, Norma, who sat with their progeny by his soon-to-be death bed. It was beautiful and, given the time and place, holds poignancy for all who were there. Being Ken, it deftly combined the lyrical with the mundane, the confessional with the aspirational.

Earlier in life his children, perhaps not yet as appreciative of his gifts and talents as they grew to be, were surrounded by poetry. We had it, old and new, in books that streamed into the house and were stored in the most surprising places – they seemed to be in every room. Dad was poetry editor and a reviewer at the Catholic Weekly and sometimes, if he thought we were up to it, some of us got a chance at assessing the efforts of others.

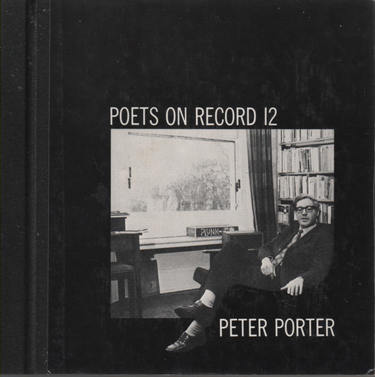

My sister Marea specialised in recordings. University of Queensland Press issued some 45s featuring the leading literary lights of the day. Marea was studying for exams at one point, so a young journalist in her brother was commissioned to appreciate the tones and texts of four poets captured on vinyl. That is how I came to have on my shelves Volumes 9 to 12 of Poets On Record – Judith Wright, Chris Wallace-Crabbe, Randolph Stow and Peter Porter.

In the cover photograph on his disc Porter sits with crossed legs in a lounge chair with a row of books behind him. In shot there is part of a desk, a stool but, intriguingly, on a shelf above the radiator beneath a window of what I assume was his London home is a box containing the 1960s children’s game, Kerplunk. I assume it was his daughters’.

It was certainly an adult conversation we engaged in when I happened to meet the poet, a few beers on, at the Harold Park pub in Sydney, where Porter had given a reading as part of that boozer’s 1980’s eclectic arts programme. He even gave theatre director Adam Quinn and me permission to use his poetry in a show we spoke about but never got round to putting together.

Volume 12 of Poets On Record contains some of Porter’s greatest hits – Phar Lap in the Melbourne Museum, Mort aux Chats and Your Attention, Please. He was a mighty figure of Australian letters, who spent most of his life in London. Indeed, we exchanged cards after the publication of his last volume, Better Than God, which appeared in his eightieth year, the one before his death. My wife told me I would regret throwing away his handwritten postcard, which I do. The memory sits with the one of my finding myself seated next to playwright Arthur Miller at the National Theatre and being ‘too English’ to speak with him, even to tell him how much his work had meant to me as an actor. I had played three parts in different productions of vastly ranging quality of his play, The Crucible. But that, as they say, is another story.

When my father died I inherited, mainly through the offices of my siblings, most of his collection of poetry books. It was added to my own which contains works by Dad himself and some of my first published efforts in the art form. Like all writers, our achievements are mixed; we do not always produce gold. In fact, to my embarrassment, one of the most pedestrian and dull works I ever managed to produce made it into print. Many works at the other end of the quality spectrum did not, either because the editors did not warm to them, or I no longer had the stomach for a rejection slip if I sent them off.

For people like Porter and my father poetry was a vocation, though Ken had to earn a living as a journalist. For others, it is a passion, a pastime, a part of a life made up of many demands and duties. My brother Paul has produced two volumes, An Existential Grammar and Suture Lines, and is currently doing a doctorate at Sydney University. His business skills, not surprisingly, made him attractive to Australian Poetry, who recruited him for the board.

An online course offered by Live Canon lured me back to a structured engagement with the art form. The course content was of a high quality, though not quite matched, because of a bereavement, by its administration and liaison with participants. Having said that, it got me back in the poetic saddle, and Experimenting With Form saw this writer embracing hitherto unembraced villanelles and sestinas.

This latter form is a poem with six stanzas of six lines and a final triplet, all stanzas having lines with the same words in a varying sequence. It caught my imagination and one, As It Is, was longlisted for Live Canon’s Poetry Prize and will be published in their 2017 Anthology.

The summer also saw my colleague, The Revd Erin Clark, ordained priest. There is no shortage of poems, good and bad, that have been written to commemorate such an event. The renewed interest in poetry and vocation led to the writing of the following poem, which I hope explains itself. You can judge its quality.

TO A NEW PRIEST

Those hands that take the bread and wine

Are ordinary but special too. They are the same

As everyone else’s. Like his. Yet it’s been decided somehow –

We know the system and the process, but not the why -

To allow those fingers to take the elements and, by grace,

Embody all that for those who gather.

So much thought can be made to gather

Around those staples: bread and, for the drinker, wine

Which, still to some people’s amazement, are preceded by Grace

Before the meal. And after too. The same

Word but a different form of words. Why

That should be God-ponderers can work out somehow.

Because it is the sum of this that somehow

Breaks through the presence of those who gather

For just that – brokenness – when, how and why

Is still the work of those Theo-thinkers, who wine

And dine on ideas that chew over the same

Simple stuff of wheat and grape which grace

The ornate tables and ordinary altars that speak of grace.

Unbroken in crushed and strained grape and grain, somehow

Surviving as they are, but turning in the hearts of the same

Worthy but still unworthy recipients. The crumbs of life gather

To collect with drips of bloodied fruit, fortified wine

That fortifies the gathered. All given in love. Love? Why

Else would we need to know the why

And wherefore of this sustaining grace

That sees now your hands – holy hands – fumble with wafer and wine,

Jittery, as the stumbling firsts of all actions, somehow

Emboldened when body and mind seek to gather

The lost threads of dead darkness transformed? The same

Yesterday, today and tomorrow. A time of same-

Ness shattered in love. That is why

We need to recall the events done once for all. We gather

To celebrate the living death story of his grace

That, other-worldly as it must be, is somehow

Made manifest each earthly time in bread and wine.

The prayers we gather over bread and wine

Are newly the same endlessly in time. Why? Somehow

In every time and clime, he leads us to embrace his grace.

© Kevin Scully

June 2017

Earlier in life his children, perhaps not yet as appreciative of his gifts and talents as they grew to be, were surrounded by poetry. We had it, old and new, in books that streamed into the house and were stored in the most surprising places – they seemed to be in every room. Dad was poetry editor and a reviewer at the Catholic Weekly and sometimes, if he thought we were up to it, some of us got a chance at assessing the efforts of others.

My sister Marea specialised in recordings. University of Queensland Press issued some 45s featuring the leading literary lights of the day. Marea was studying for exams at one point, so a young journalist in her brother was commissioned to appreciate the tones and texts of four poets captured on vinyl. That is how I came to have on my shelves Volumes 9 to 12 of Poets On Record – Judith Wright, Chris Wallace-Crabbe, Randolph Stow and Peter Porter.

In the cover photograph on his disc Porter sits with crossed legs in a lounge chair with a row of books behind him. In shot there is part of a desk, a stool but, intriguingly, on a shelf above the radiator beneath a window of what I assume was his London home is a box containing the 1960s children’s game, Kerplunk. I assume it was his daughters’.

It was certainly an adult conversation we engaged in when I happened to meet the poet, a few beers on, at the Harold Park pub in Sydney, where Porter had given a reading as part of that boozer’s 1980’s eclectic arts programme. He even gave theatre director Adam Quinn and me permission to use his poetry in a show we spoke about but never got round to putting together.

Volume 12 of Poets On Record contains some of Porter’s greatest hits – Phar Lap in the Melbourne Museum, Mort aux Chats and Your Attention, Please. He was a mighty figure of Australian letters, who spent most of his life in London. Indeed, we exchanged cards after the publication of his last volume, Better Than God, which appeared in his eightieth year, the one before his death. My wife told me I would regret throwing away his handwritten postcard, which I do. The memory sits with the one of my finding myself seated next to playwright Arthur Miller at the National Theatre and being ‘too English’ to speak with him, even to tell him how much his work had meant to me as an actor. I had played three parts in different productions of vastly ranging quality of his play, The Crucible. But that, as they say, is another story.

When my father died I inherited, mainly through the offices of my siblings, most of his collection of poetry books. It was added to my own which contains works by Dad himself and some of my first published efforts in the art form. Like all writers, our achievements are mixed; we do not always produce gold. In fact, to my embarrassment, one of the most pedestrian and dull works I ever managed to produce made it into print. Many works at the other end of the quality spectrum did not, either because the editors did not warm to them, or I no longer had the stomach for a rejection slip if I sent them off.

For people like Porter and my father poetry was a vocation, though Ken had to earn a living as a journalist. For others, it is a passion, a pastime, a part of a life made up of many demands and duties. My brother Paul has produced two volumes, An Existential Grammar and Suture Lines, and is currently doing a doctorate at Sydney University. His business skills, not surprisingly, made him attractive to Australian Poetry, who recruited him for the board.

An online course offered by Live Canon lured me back to a structured engagement with the art form. The course content was of a high quality, though not quite matched, because of a bereavement, by its administration and liaison with participants. Having said that, it got me back in the poetic saddle, and Experimenting With Form saw this writer embracing hitherto unembraced villanelles and sestinas.

This latter form is a poem with six stanzas of six lines and a final triplet, all stanzas having lines with the same words in a varying sequence. It caught my imagination and one, As It Is, was longlisted for Live Canon’s Poetry Prize and will be published in their 2017 Anthology.

The summer also saw my colleague, The Revd Erin Clark, ordained priest. There is no shortage of poems, good and bad, that have been written to commemorate such an event. The renewed interest in poetry and vocation led to the writing of the following poem, which I hope explains itself. You can judge its quality.

TO A NEW PRIEST

Those hands that take the bread and wine

Are ordinary but special too. They are the same

As everyone else’s. Like his. Yet it’s been decided somehow –

We know the system and the process, but not the why -

To allow those fingers to take the elements and, by grace,

Embody all that for those who gather.

So much thought can be made to gather

Around those staples: bread and, for the drinker, wine

Which, still to some people’s amazement, are preceded by Grace

Before the meal. And after too. The same

Word but a different form of words. Why

That should be God-ponderers can work out somehow.

Because it is the sum of this that somehow

Breaks through the presence of those who gather

For just that – brokenness – when, how and why

Is still the work of those Theo-thinkers, who wine

And dine on ideas that chew over the same

Simple stuff of wheat and grape which grace

The ornate tables and ordinary altars that speak of grace.

Unbroken in crushed and strained grape and grain, somehow

Surviving as they are, but turning in the hearts of the same

Worthy but still unworthy recipients. The crumbs of life gather

To collect with drips of bloodied fruit, fortified wine

That fortifies the gathered. All given in love. Love? Why

Else would we need to know the why

And wherefore of this sustaining grace

That sees now your hands – holy hands – fumble with wafer and wine,

Jittery, as the stumbling firsts of all actions, somehow

Emboldened when body and mind seek to gather

The lost threads of dead darkness transformed? The same

Yesterday, today and tomorrow. A time of same-

Ness shattered in love. That is why

We need to recall the events done once for all. We gather

To celebrate the living death story of his grace

That, other-worldly as it must be, is somehow

Made manifest each earthly time in bread and wine.

The prayers we gather over bread and wine

Are newly the same endlessly in time. Why? Somehow

In every time and clime, he leads us to embrace his grace.

© Kevin Scully

June 2017

RSS Feed

RSS Feed