Perfectionism is a peculiar blessing and curse. It can bring about excellence, a comparative needed to allow the brightest and best to shine. It can, however, become something of an inhibitor on an individual or society. I have written about the clash of those elements and how it affect(ed)(s) me in Three Angry Men.

When my first book was published it produced that feeling spoken of by parents of their first newborn—euphoria, delight and anxiety. The hard slog of pregnancy, the joyous terror of labour and childbirth seemingly evaporated as I held my progeny and wondered at its future.

As nervous parents await the result of a baby check—is there something ‘wrong’ with the child?—I scanned the pages with concern only to find my self confronted with a solecism, a feminine job title.

The parental need to know and blame ensued. Was it on my side, or was there something about the process of growth and development, external environmental factors, that led to this?

The word shocked me profoundly. I had, as a journalist, been an activist to have gender-specific professional words—authoress, WPC, stewardess—removed from journalese, allowing employment to take precedence over gender.

An investigation into the process followed, as publishing in the corporate sector allows no voice to sing alone. My initial typescript had been read by the commissioning editor who suggested a number of changes—necessary and improving—the subsequent draft overseen by a process editor, again with feedback to the author, proofs read by writer and a proofreader. It was this last professional eye that had made the offending ‘correction’.

For all that, the slip was not that monumental. A collector’s item of particular delight is The Sinner’s Bible or The Wicked Bible which has God’s injunction, ‘Thou shalt commit adultery’.

Time is not in itself a corrective. Rushing, of course, can cause its own problems but in the time-pressurised old world of print journalism the aforementioned checks and balances caught many bloopers before the papers hit the streets. Like fish, it is the ones that got away that cause embarrassment.

I recall a front page story of an award of damages to a patient whose surgeon had erred in the amputation of a limb. Evidence had been given that it should have been the left leg that required surgery. The text of the article was consistent on this. What put the mockers on the front page splash was the reversal of the image should showed the wronged patient minus his right leg.

When my first book was published it produced that feeling spoken of by parents of their first newborn—euphoria, delight and anxiety. The hard slog of pregnancy, the joyous terror of labour and childbirth seemingly evaporated as I held my progeny and wondered at its future.

As nervous parents await the result of a baby check—is there something ‘wrong’ with the child?—I scanned the pages with concern only to find my self confronted with a solecism, a feminine job title.

The parental need to know and blame ensued. Was it on my side, or was there something about the process of growth and development, external environmental factors, that led to this?

The word shocked me profoundly. I had, as a journalist, been an activist to have gender-specific professional words—authoress, WPC, stewardess—removed from journalese, allowing employment to take precedence over gender.

An investigation into the process followed, as publishing in the corporate sector allows no voice to sing alone. My initial typescript had been read by the commissioning editor who suggested a number of changes—necessary and improving—the subsequent draft overseen by a process editor, again with feedback to the author, proofs read by writer and a proofreader. It was this last professional eye that had made the offending ‘correction’.

For all that, the slip was not that monumental. A collector’s item of particular delight is The Sinner’s Bible or The Wicked Bible which has God’s injunction, ‘Thou shalt commit adultery’.

Time is not in itself a corrective. Rushing, of course, can cause its own problems but in the time-pressurised old world of print journalism the aforementioned checks and balances caught many bloopers before the papers hit the streets. Like fish, it is the ones that got away that cause embarrassment.

I recall a front page story of an award of damages to a patient whose surgeon had erred in the amputation of a limb. Evidence had been given that it should have been the left leg that required surgery. The text of the article was consistent on this. What put the mockers on the front page splash was the reversal of the image should showed the wronged patient minus his right leg.

With that in mind, self-publishing presents a minefield of opportunities for gremlins to creep in—the original draft, the revised typing, the imperfectly set proof, the slovenly read-through, the improperly reset and reviewed text.

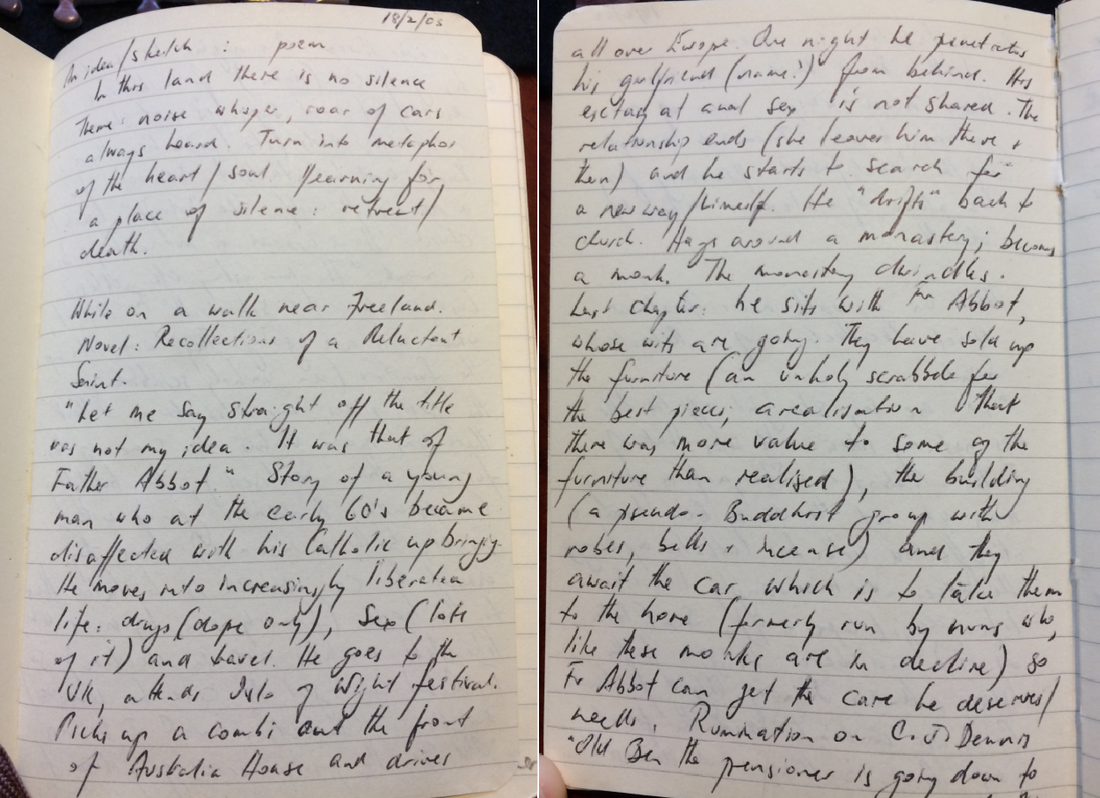

The Rest is Silence was not produced in haste. Indeed, the first outline of its plot was recorded in my commonplace book in 2003.

In the preparation of the e-book and paperback a number of drafts were gone through. In one, I realised a very mild example of the form—an added ‘e’ appeared in a name, punning on the title of a poem and song. I corrected the name but distractedly put in the original, rather than the punned, title.

Of course, I have now come to realise that there are other small mistakes. I could, of course, revise the editions, and may in time. Or even issue some Errata. But, to quote Pilate, and allow myself to move on, it is best to say ‘Quod scripsi scripsi’ ('What I have written, I have written'.) As for the errors, for the moment I will leave it for others to point them out.

The Rest is Silence was not produced in haste. Indeed, the first outline of its plot was recorded in my commonplace book in 2003.

In the preparation of the e-book and paperback a number of drafts were gone through. In one, I realised a very mild example of the form—an added ‘e’ appeared in a name, punning on the title of a poem and song. I corrected the name but distractedly put in the original, rather than the punned, title.

Of course, I have now come to realise that there are other small mistakes. I could, of course, revise the editions, and may in time. Or even issue some Errata. But, to quote Pilate, and allow myself to move on, it is best to say ‘Quod scripsi scripsi’ ('What I have written, I have written'.) As for the errors, for the moment I will leave it for others to point them out.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed