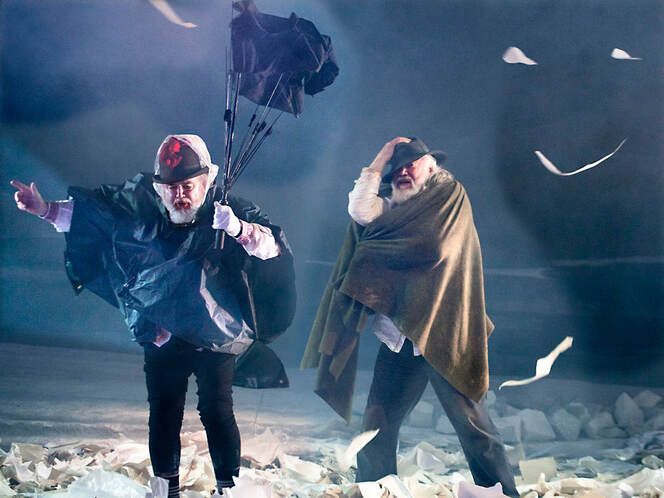

Louise Alder (Cordelia) and John Tomlinson (Lear)

Louise Alder (Cordelia) and John Tomlinson (Lear) There has been an understandable drought in the wastes of Learland, replenished during the Covid crisis by online offerings. It is a blessing that so many film and archival recordings are available.

To slake the thirst since my last public thoughts on this monumental piece, I have gulped from the delights of silent movies, an archival performance of Colm Feore at the Shakespeare Festival Theatre in Ontario, Canada, and Michael Hordern from a BBC Play of the Month. There was also the peculiar King of Texas, with Shakespearean Patrick Stewart as the Wild West rancher in a film that had echoes of one of my suggested takes on the play in which a pastoralist carves up his property between his daughters.

So it was with parched excitement I found myself in a theatre in rural Hampshire to see what was an experiment of sorts, with opera singers staging the play. I had seen this production had music by Nigel Osborne, so I assumed, wrongly as it turned out, to be a new opera—I could have read the background to the production before booking, but I tend not to do that in case it tarnishes an attempt at an open mind.

I had seen a production of Albert Reimann’s King Lear at the Coliseum in 1989 when the ENO decided to conform to its house policy of performing in English, replacing the German libretto with words from the Bard himself. The production was a splendid example of how to opera Germanly but with great performances nonetheless. The Grange Festival offering was not to be of this ilk.

Instead, a group of singers would present the spoken drama, as they call it in China. This, as pointed out in an article by Michael Billington in the Guardian, was to challenge the trope that opera singers are second rate actors who ‘just wave their arms around like traffic cops’.

Only three performances of this play were scheduled and even those were hit by Covid restrictions—audience members had to show proof of double vaccination and a negative lateral flow test. From an audience point of view, it was extraordinarily comfortable, with no queues at the bars and plenty of space in the auditorium.

The project harked back to the controversy some years back about those who gloried in the verse over the sense, and others accused of debasing the iambic pentameter to go for ‘modern’ expression with scant regard to metre. John Gielgud, later in life, admitted that he was prone to 'singing' the text earlier in his career. Others have been accused of being so into the role, and competing with stage effects as loud as a storm scene, of being not only incomprehensible but inaudible

To slake the thirst since my last public thoughts on this monumental piece, I have gulped from the delights of silent movies, an archival performance of Colm Feore at the Shakespeare Festival Theatre in Ontario, Canada, and Michael Hordern from a BBC Play of the Month. There was also the peculiar King of Texas, with Shakespearean Patrick Stewart as the Wild West rancher in a film that had echoes of one of my suggested takes on the play in which a pastoralist carves up his property between his daughters.

So it was with parched excitement I found myself in a theatre in rural Hampshire to see what was an experiment of sorts, with opera singers staging the play. I had seen this production had music by Nigel Osborne, so I assumed, wrongly as it turned out, to be a new opera—I could have read the background to the production before booking, but I tend not to do that in case it tarnishes an attempt at an open mind.

I had seen a production of Albert Reimann’s King Lear at the Coliseum in 1989 when the ENO decided to conform to its house policy of performing in English, replacing the German libretto with words from the Bard himself. The production was a splendid example of how to opera Germanly but with great performances nonetheless. The Grange Festival offering was not to be of this ilk.

Instead, a group of singers would present the spoken drama, as they call it in China. This, as pointed out in an article by Michael Billington in the Guardian, was to challenge the trope that opera singers are second rate actors who ‘just wave their arms around like traffic cops’.

Only three performances of this play were scheduled and even those were hit by Covid restrictions—audience members had to show proof of double vaccination and a negative lateral flow test. From an audience point of view, it was extraordinarily comfortable, with no queues at the bars and plenty of space in the auditorium.

The project harked back to the controversy some years back about those who gloried in the verse over the sense, and others accused of debasing the iambic pentameter to go for ‘modern’ expression with scant regard to metre. John Gielgud, later in life, admitted that he was prone to 'singing' the text earlier in his career. Others have been accused of being so into the role, and competing with stage effects as loud as a storm scene, of being not only incomprehensible but inaudible

Thomas Allen (Gloucester) and Robert Flaum (Edgar)

Thomas Allen (Gloucester) and Robert Flaum (Edgar) But what of the Grange Festival performance itself?

Its genesis came when Kim Begley discussed the idea with director Keith Warner in the back of a taxi. Begley, an actor who moved into opera, himself took the stage as the Fool, an assured and funny realisation that drew heavily on its classical theatre Chorus function.

The other roles were taken by operatic giants, John Tomlinson as the mad king, Thomas Allen as the blinded Gloucester, and performers better known for Wagner and Mozart rather than Shakespeare and Ayckbourn.

By and large it was a revelation. If nothing else it affirmed my suspicion that vocal training at drama schools seems not to be the major plank it was. I have seen, even at the RSC, some incisive acting cut asunder by weak vocal technique. I once made this comment to a friend working in Stratford-upon-Avon, questioning the efficacy of its once-famous voice department. ‘You can only work with what you’re presented with,’ was his maudlin comment.

It should come as no surprise that Tomlinson and his colleagues succeeded in spades where others might be struggling to be heard. Years of daily practice, singing over an orchestra, and the challenge of changing approaches to performance in the operatic world, gave a resonant clarity to text. Every word from the principals was crisp and clear.

And the acting? Like most productions, it was variable. Some rose to the challenge better than others. But there were stand out wonders: Tomlinson’s Lear, Allen’s Gloucester, Begley’s Fool, and, Susan Bullock, Emma Bell and Louise Alder as the trio of sisters, Goneril, Regan and Cordelia. Robert Flaum’s command of text and madness in Edgar and Mad Tom was exhilarating.

Billington quoted John Tomlinson: ‘When Terry Gilliam came to direct at ENO in 2011, he said he was going to drag operatic acting into the modern world. We were way ahead of him on that. In fact, I’d say that in the UK from the 1960s to the late 1990s, singers were generally very good actors. But I admit that in the last couple of decades, operatic acting has often been stymied by hi-tech design and concept-driven direction that treats the singer as one item in a visual scheme: the barer the stage, the better the acting.’

He proved his point.

Its genesis came when Kim Begley discussed the idea with director Keith Warner in the back of a taxi. Begley, an actor who moved into opera, himself took the stage as the Fool, an assured and funny realisation that drew heavily on its classical theatre Chorus function.

The other roles were taken by operatic giants, John Tomlinson as the mad king, Thomas Allen as the blinded Gloucester, and performers better known for Wagner and Mozart rather than Shakespeare and Ayckbourn.

By and large it was a revelation. If nothing else it affirmed my suspicion that vocal training at drama schools seems not to be the major plank it was. I have seen, even at the RSC, some incisive acting cut asunder by weak vocal technique. I once made this comment to a friend working in Stratford-upon-Avon, questioning the efficacy of its once-famous voice department. ‘You can only work with what you’re presented with,’ was his maudlin comment.

It should come as no surprise that Tomlinson and his colleagues succeeded in spades where others might be struggling to be heard. Years of daily practice, singing over an orchestra, and the challenge of changing approaches to performance in the operatic world, gave a resonant clarity to text. Every word from the principals was crisp and clear.

And the acting? Like most productions, it was variable. Some rose to the challenge better than others. But there were stand out wonders: Tomlinson’s Lear, Allen’s Gloucester, Begley’s Fool, and, Susan Bullock, Emma Bell and Louise Alder as the trio of sisters, Goneril, Regan and Cordelia. Robert Flaum’s command of text and madness in Edgar and Mad Tom was exhilarating.

Billington quoted John Tomlinson: ‘When Terry Gilliam came to direct at ENO in 2011, he said he was going to drag operatic acting into the modern world. We were way ahead of him on that. In fact, I’d say that in the UK from the 1960s to the late 1990s, singers were generally very good actors. But I admit that in the last couple of decades, operatic acting has often been stymied by hi-tech design and concept-driven direction that treats the singer as one item in a visual scheme: the barer the stage, the better the acting.’

He proved his point.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed