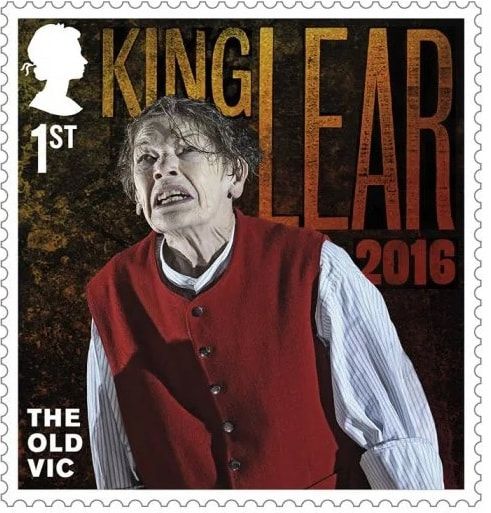

It was a stamp that did it. There, sitting in my pigeon hole at work, was a letter, boldly addressed to me but with a stamp announcing in capital letters, King Lear.

The label that guaranteed delivery was affixed to the top of the envelope and carried the image of a raging monarch, played by Glenda Jackson on her return to the stage (a role she is reprising on Broadway) after 23 years in parliament. It is part of a Royal Mail series to mark the bicentenary of The Old Vic Theatre in London.

Mistakenly believing that the stamp had been chosen solely for my delight and entertainment, I was somewhat deflated to learn that the contents of the epistle were related, pleasantly enough as it turned out, to the business of the College where I serve.

Having sparked my interest, I have since gone on to ponder how much of the play is a meditation on communication. And the role letters play in the drama.

The opening scene, and the sub-plots, hinge on what is said, what is not, how things are couched in language and to what extent truth, subterfuge and lies play a part in the machinations of the lives of Shakespeare’s characters.

Kent is banished for challenging the decision of Lear to expel his youngest daughter whose only fault, we come to learn, is that she does not practise ‘that glib and oily art’ of her sisters ‘to speak and purpose not’.

Edmund succeeds in estranging his brother Edgar from their father’s affections by a counterfeit missive which lures Gloucester into believing his legitimate issue has designs that seek to upend the established order that ‘keeps our fortunes from us till our oldness cannot relish them’.

After that the mail flies fast and furious: Oswald is despatched to Gloucester’s, where he meets the now disguised Kent bringing a communication from his master, to warn of goings-on at home; the scheming daughters send messages to Edmund to win his heart and body; Lear’s loyal retainer gets word to the king’s banished daughter; a dying Edmund gives a note to a guard which contains a commission that should see Lear and Cordelia killed.

In a final indignity Goneril, who leaves to stab herself after poisoning her sister Regan, has her own handwriting flung at her by an outraged husband, Albany, telling her to ‘Shut your mouth, dame, or with this paper shall I stopple it.’

One of my first teenage holiday jobs was a telegram boy. I went on to be a casual postal worker, walking the streets of a suburb in western Sydney to be chased by dogs, get sunburned and deliver the mail, eventually climbing to the dizzy heights of a night sorter. I even considered, for a brief delusory period, this as an option for a full time job, thinking I would be able to write during the day.

It was inevitable that you spend time thinking what might be held in the envelopes and packages you carry on your back, or push in your trolley, or however the messages are transported. At no time did I link this to King Lear.

Which, I now come to see, was a shame. After all, I was well placed, as Kent in the guise of Caius was, to have been told that, ‘If your diligence be not speedy, I shall be there before you’.

The label that guaranteed delivery was affixed to the top of the envelope and carried the image of a raging monarch, played by Glenda Jackson on her return to the stage (a role she is reprising on Broadway) after 23 years in parliament. It is part of a Royal Mail series to mark the bicentenary of The Old Vic Theatre in London.

Mistakenly believing that the stamp had been chosen solely for my delight and entertainment, I was somewhat deflated to learn that the contents of the epistle were related, pleasantly enough as it turned out, to the business of the College where I serve.

Having sparked my interest, I have since gone on to ponder how much of the play is a meditation on communication. And the role letters play in the drama.

The opening scene, and the sub-plots, hinge on what is said, what is not, how things are couched in language and to what extent truth, subterfuge and lies play a part in the machinations of the lives of Shakespeare’s characters.

Kent is banished for challenging the decision of Lear to expel his youngest daughter whose only fault, we come to learn, is that she does not practise ‘that glib and oily art’ of her sisters ‘to speak and purpose not’.

Edmund succeeds in estranging his brother Edgar from their father’s affections by a counterfeit missive which lures Gloucester into believing his legitimate issue has designs that seek to upend the established order that ‘keeps our fortunes from us till our oldness cannot relish them’.

After that the mail flies fast and furious: Oswald is despatched to Gloucester’s, where he meets the now disguised Kent bringing a communication from his master, to warn of goings-on at home; the scheming daughters send messages to Edmund to win his heart and body; Lear’s loyal retainer gets word to the king’s banished daughter; a dying Edmund gives a note to a guard which contains a commission that should see Lear and Cordelia killed.

In a final indignity Goneril, who leaves to stab herself after poisoning her sister Regan, has her own handwriting flung at her by an outraged husband, Albany, telling her to ‘Shut your mouth, dame, or with this paper shall I stopple it.’

One of my first teenage holiday jobs was a telegram boy. I went on to be a casual postal worker, walking the streets of a suburb in western Sydney to be chased by dogs, get sunburned and deliver the mail, eventually climbing to the dizzy heights of a night sorter. I even considered, for a brief delusory period, this as an option for a full time job, thinking I would be able to write during the day.

It was inevitable that you spend time thinking what might be held in the envelopes and packages you carry on your back, or push in your trolley, or however the messages are transported. At no time did I link this to King Lear.

Which, I now come to see, was a shame. After all, I was well placed, as Kent in the guise of Caius was, to have been told that, ‘If your diligence be not speedy, I shall be there before you’.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed