Does it matter who speaks the last line in a drama?

Some years back I developed a personal working method for necessary components before writing a play. No word could be put down on paper until three elements were clear – how it started; what happened before the interval (when drink and loo breaks were compulsory); and how it ended.

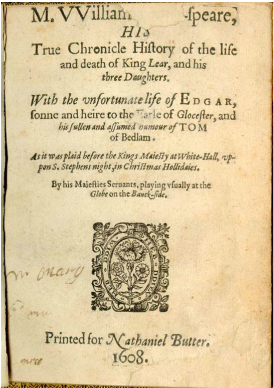

Last lines matter. (A company once changed the ending of one of my plays without consulting me, but that’s another story.) In the current rash of King Lears, to coincide with death of William Shakespeare 400 years ago, I find I have developed an heightened expectation toward the close of play.

Who will speak the final lines? Will they come out of the mouth of Albany or Edgar? Given the vastly different experiences each has undergone – Edgar betrayed, disguising himself for self-preservation only to protect his abused and deluded father; Albany, the ‘milk-livered man’ in his wife’s eye, who goes on to command forces to victory in battle. Does it matter?

Perhaps we shouldn’t start from there, as the joke goes. The question should be how did there come to be such variations? Fortunately, bigger brains than mine have sought to deal with this. The mystery lies in how the plays were preserved – in the Quarto or Folio editions.

Dr Christie Carson, from the Royal Holloway University of London, in an article from the View From the Experts section of the British Library website, says

'The final lines of the play in the Quarto are given to Albany, which is appropriate in terms of his seniority within the social structure to the play. However, in the Folio these lines are given to Edgar, the only person on stage who has not engaged in the battle between the generations until the very last scene. Edgar is presented in the Folio as the leader of the new generation and the representative of a gentler form of leadership.

'Albany (Q) Edgar (F) The weight of this sad time we must obey,

Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say.

The oldest have borne most; we that are young

Shall never see so much, nor live so long. [300]

[Exeunt with a dead march]

'Edgar ending the play introduces hope of a new beginning with a different set of values in place. As Richard Eyre, who directed the play at the National Theatre in 1997, says "there is something wonderful about this terribly simple advice being given to you by a man who has had to grow up in the most violent way. Edgar, a sort of mild, bookish man, becomes a warrior, then sees this holocaust, and the advice he gives you is, 'open your heart, speak what you feel'".

'I suggest, then, that there is strong evidence the changes between the Quarto and the Folio were made as a result of the audience response to the play during Shakespeare’s lifetime. The ending, in particular, is altered to change it from a scene of absolute despair to a scene of possible redemption and rebirth. Hope is reintroduced into the Folio ending of the play, something that makes this tragedy more poignant but also more bearable in its Folio form.'

The contention is that, even then, authors would try out material and change it according to taste. What a shame writers today aren’t given such a chance to see their plays a second time, let alone tinker with them.

(With thanks to Dr Carson for permission to quote her Expert View.)

Some years back I developed a personal working method for necessary components before writing a play. No word could be put down on paper until three elements were clear – how it started; what happened before the interval (when drink and loo breaks were compulsory); and how it ended.

Last lines matter. (A company once changed the ending of one of my plays without consulting me, but that’s another story.) In the current rash of King Lears, to coincide with death of William Shakespeare 400 years ago, I find I have developed an heightened expectation toward the close of play.

Who will speak the final lines? Will they come out of the mouth of Albany or Edgar? Given the vastly different experiences each has undergone – Edgar betrayed, disguising himself for self-preservation only to protect his abused and deluded father; Albany, the ‘milk-livered man’ in his wife’s eye, who goes on to command forces to victory in battle. Does it matter?

Perhaps we shouldn’t start from there, as the joke goes. The question should be how did there come to be such variations? Fortunately, bigger brains than mine have sought to deal with this. The mystery lies in how the plays were preserved – in the Quarto or Folio editions.

Dr Christie Carson, from the Royal Holloway University of London, in an article from the View From the Experts section of the British Library website, says

'The final lines of the play in the Quarto are given to Albany, which is appropriate in terms of his seniority within the social structure to the play. However, in the Folio these lines are given to Edgar, the only person on stage who has not engaged in the battle between the generations until the very last scene. Edgar is presented in the Folio as the leader of the new generation and the representative of a gentler form of leadership.

'Albany (Q) Edgar (F) The weight of this sad time we must obey,

Speak what we feel, not what we ought to say.

The oldest have borne most; we that are young

Shall never see so much, nor live so long. [300]

[Exeunt with a dead march]

'Edgar ending the play introduces hope of a new beginning with a different set of values in place. As Richard Eyre, who directed the play at the National Theatre in 1997, says "there is something wonderful about this terribly simple advice being given to you by a man who has had to grow up in the most violent way. Edgar, a sort of mild, bookish man, becomes a warrior, then sees this holocaust, and the advice he gives you is, 'open your heart, speak what you feel'".

'I suggest, then, that there is strong evidence the changes between the Quarto and the Folio were made as a result of the audience response to the play during Shakespeare’s lifetime. The ending, in particular, is altered to change it from a scene of absolute despair to a scene of possible redemption and rebirth. Hope is reintroduced into the Folio ending of the play, something that makes this tragedy more poignant but also more bearable in its Folio form.'

The contention is that, even then, authors would try out material and change it according to taste. What a shame writers today aren’t given such a chance to see their plays a second time, let alone tinker with them.

(With thanks to Dr Carson for permission to quote her Expert View.)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed